…and a woolly New Year! (Oh, ok! It’s not the best pun, but I did try!)

My lovelyfella has sweetly been trying to think of British-based knittery things for my Christmas, Gorgeous thing that he is! I did give him a few starting points, but I will be excited to see on Christmas day what he has picked out! (can’t be too hard, right?!)

With only another couple of weeks of gift buying time left, if you have a knitter in your life and you are not sure what to buy for them, or you are a knitter yourself and you want to treat yourself this Christmas then I have a few gift ideas for you. All lovely makers, sellers and artists are UK based and most of the items are made in Britain, too!

I have recently been introduced to Kettle Yarn Co via the wonderful world of Twitter! Linda is a Canadian dyer living in London. She dyes predominantly in British yarns and the colours have a real lustrous glow. Linda’s BFL mini-skeins are really something. Get a load of these colours!

Linda says on her blog that she will even wrap the skeins up for the person you are buying for and send them directly! You cannot say better than that in terms of a quality present and attention to detail! The skein pairs are £14 each and numbers are limited, so get in there quick!

ooOOoo

I have been coveting a pretty yarn bowl for a very long time. I think they are not only practical, but they are very pleasing to look at! I think some of the prettiest bowls are from Little Wren Pottery. Based in Northallerton, Yorkshire, there are lots of styles to choose from and prices range from £12 to £18 – a very reasonable price for a beautiful, hand made item! You can even have them personalised with the giftee’s name. Please be aware Little Wren Pottery have last date orders for Christmas gifts, please check the shop out for details)

Fyberspates also have a wonderful line of pottery yarn bowls, very local to them and if you miss out on the posting deadline for Little Wren, you definitely should check out these very special bowls. They retail at £25 and again I think they’d be so beautiful on display as well as a practical tool!

ooOOoo

I have been showing lovelyfella these pins at every opportunity! They are felted Shetland jumpers and they are the creation of Shetland designer Donna Smith.

Donna has a beautiful range of felt items from scarves and bags, to hair pins and brooches and also really lovely festive tree decorations. You can visit her store at Not On The High Street. Prices range from £5.95 for hairpins to £11.95 for the jumper brooches.

ooOOoo

Of course, if you are giving woolly gifts, you may also like to take the theme further!

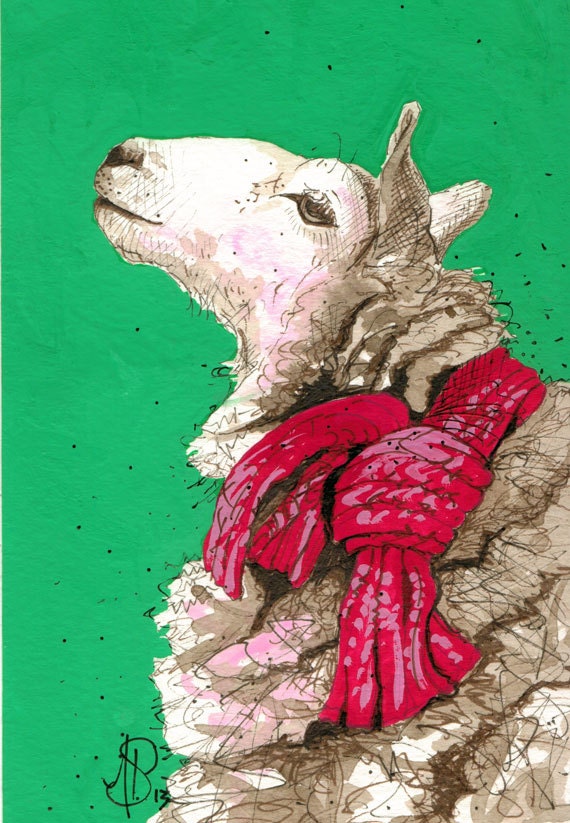

Angela Simpson’s sheepy Christmas cards are really quirky and fun and you can buy them from the Highland’s based illustrator for £2.50 each or pick and mix the entire range for 5 for £10

ooOOoo

And, if you do not mind spending a little bit extra on the stuff that often gets ripped off and screwed up in the bin you can get this super cute wrapping paper. I think it doesn’t necessarily have to have snowflakes, snowmen and Santa on it to make it festive – I mean, woolly jumpers are VERY festive.

Mary Kilvert, based in Frome, has this wrap and so many other lovely sheepy goods in her Etsy shop – from cushions, bags and mugs to charity Christmas cards. The gift wrap is £10 for 5 sheets and, actually, don’t you think it would make a lovely addition to a knitter’s wall, if you put it in a clip frame?!

ooOOoo

Back to the wools now! I have been really eagerly awaiting the launch of John Arbon’s new Viola range. The 100 % merino DK yarn is spun at their new mill and costs £12.50 per 100g hank. I love how the yarn look almost hand-painted look – those flecks of light are very lovely indeed.

The skeins are not in the shop yet, but will be available very soon. You can register your interest in the yarn via the website.

ooOOoo

If you are unsure of the knitting ability of the gift-getter then the The Little Knit Kit Company is a good place to go! Based in West Glamorgan, they have a range of kits, all made in Britain, that will appeal to many knitters. The kits are all aimed at knitters with a beginners ability, but show you just what kind of wonderful things you can create with simple techniques! I adore the seaside cottage and the gingerbread house kits

The kits – of all shapes and sizes – start at about £10 and go up to around £30. They even have British made needles to knit them with!

ooOOoo

Let us not forget that spinners need gifts too! I am a very occasional spinner, but one of these kits from Hilltop Cloud would encourage me to pick up the spindle a bit more!

Gorgeous colours and textures, a spindle and beginner instructions to spin your own wool – and at £15, this is a really great and thoughtful gift idea for the fibre lover in your life.

I really like the spinners project bags available through the Hilltop Cloud etsy store too.

And – as a small aside – if spinning is your friend’s bag one of my favourite podcasters, Nic from Yarns from the Plain has opened an etsy shop selling British fibre tops and yarn, which she has dyed herself. This is a relatively new venture for Nic, please keep checking the shop for updates. All the very best with the new shop Nic!

ooOOoo

And of course, knitters do like project bags! I do really like the styles and print choices of AndSewToKnit, like this groovy model!

Finally, do not forget the notions! We knitters love our stitch markers, buttons, finishings, tapes, etc and they really make great stocking fillers.

Stitch Markers and Tin from Rosie Retro on Etsy (Click on pic)

Tape from Fripperies & Biblots

Buttons from Owl Print Panda

I hope this has given you a few ideas; it is very satisfying to buy things which were made, grown, dyed or sourced on your own doorstep! Happy shopping!

And don’t forget that right here on KnitBritish you can win an entire British wool stash. Over 1 kg of British wool! If you have not already entered in the various ways GO HERE, Comment and enter!

Do you need another sneaky peak of what is inside the stash? Maybe I will tease you tomorrow!

![IMG_3161[1]](https://woolwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/IMG_31611-528x396.jpg)

![IMG_3116[1]](https://woolwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/IMG_31161-528x396.jpg)

![IMG_3164[1]](https://woolwork.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/IMG_31641-e1377789660214-528x704.jpg)